In today’s political landscape, the failures of capitalism and the stark inequality between the rich and the poor are commonly accepted. However, economic redistribution remains a taboo topic, even within left-leaning parties. This reluctance stems from what I define as "the defeat of labour"—not merely the historical decline of the labour movement in the 20th century, but a broader theoretical defeat that has rendered the concept of redistribution unthinkable.

The defeat of labour signifies the ascendance of capital as the sole source of value in society, where individuals are seen primarily as rational entrepreneurs striving to maximise their capital assets, whether social, cultural, or economic. Marx’s critique of capitalism revolved around the category of labour because it served as the foundation for advocating universal economic redistribution and abolishing capitalist relationships of production.

Marx sharply critiqued philosophical idealism, emphasising that human beings are sensual, productive creatures who engage with each other and their environments through labour. This understanding is crucial for any claim to redistribution. Idealist perspectives, even when charitable, often treat capital as the genuine source of value while relegating labour to a mere accessory.

In a capitalist society, valuable labour is narrowly defined, typically highlighting profitable activities and introducing alienation through the separation of intellectual and physical work, as well as through gendered and racialised divisions of labour. While alienation was perceived as a natural phenomenon prior to capitalism, bourgeois society has shifted the narrative to emphasise individual freedom, thus de-naturalising alienation. Nonetheless, capitalism relies on this alienation for profit extraction and to maintain the bourgeois class. The working class becomes the overlooked foil to the bourgeois ideology of individual freedom.

Marx envisioned communism as the synthesis of the bourgeois thesis of individual freedom and the antithesis of capitalist alienation, culminating in a collective freedom realised through free labour. However, contemporary political discourse has shifted towards recognising individual freedom in a cultural capital context, aiming to address various exclusions within the bourgeois framework—class, race, gender, and more. Unfortunately, this focus on individual rights sidelines the need for economic redistribution, framing class merely as a cultural identity rather than a form of systemic alienation to be overcome. Moreover, it fits well with the superficial corporate concern for the diversification of employment and with their main interest, the protection of profits.

Consequently, a rational public discourse supporting economic redistribution is nearly non-existent. In modern thought, the focus has shifted from class struggles to cultural identities; everyone is seen as a bourgeois subject with the inherent right to live authentically, as long as they obey the capitalist demands. When economic redistribution is mentioned, it is often couched in terms of humanitarian aid rather than a fundamental economic restructuring.

Fundamentally, the issue of inequality lies in the separation of labourers from the means of production. This dispossession is crucial for reproducing capitalist relationships, regardless of the superficial ownership of some of the means of production by individual workers. The concept of poverty complicates this further, often attributed to various individual ailments or adverse conditions rather than to the systemic needs of capital. While leftist solutions suggest improving medical and educational services, these are contingent upon a growing economy. When growth stagnates, austerity and the privatisation of public services are typically enforced. In fact, under neoliberalism, austerity and privatisation have become the norm regardless of the state of the economy.

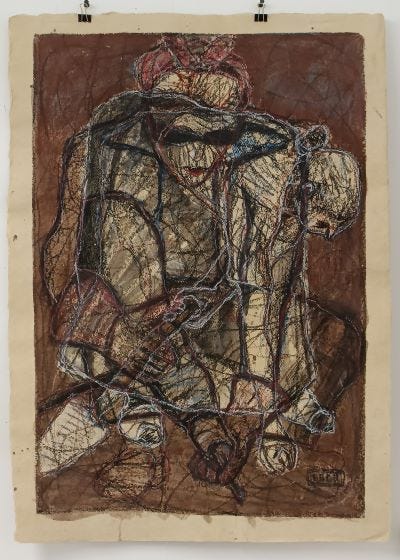

Moreover, taxation—the source of funding for public services—has been reinterpreted as wealth alienation from its "rightful" owners. The prevailing perception today underscores the defeat of labour; labour is often equated with alienation, illustrated by depictions like the iconic assembly line in “Modern Times”, while capital is celebrated as a manifestation of talent and creativity.

The defeat of labour has made economic redistribution impossible, relegating it to the margins of political dialogue. Labour, once the driving force behind demands for equality, has been overshadowed by a capitalist narrative that glorifies individualism and capital. For meaningful discourse on economic redistribution to resurface, it is imperative to reclaim the category of labour and reconceptualise it as central to discussions about justice and equity in our society. By doing so, we can challenge the structures of alienation that continue to perpetuate inequality.